Panthéon (Church of Sainte Geneviève)

1758-90, Paris, France

The Panthéon in the late 19th century. Photo courtesy Columbia University, Ware Library Photo Collection.

According to her Vita, Sainte Geneviève was born a peasant girl at Nanterre around 420 AD. Encouraged by Saint Germain of Auxerre, she chose the life of a nun and later moved to Paris, where she was soon admired for her pious and ascetic life and her charitable deeds. When Attila and his Huns threatened to conquer Paris in 451, Geneviève is said to have convinced the city's inhabitants to remain steadfast and not to leave their homes. Attila eventually abandoned his plans to capture the city and Geneviève's prayers were considered to have affected this outcome. Following the Frankish conquest of Paris in 464, Genevieve's influence with the Merovingian rulers once again saved many lives. Shortly before her death in 512, King Clovis followed Geneviève's wishes and built a church in honor of Saints Peter and Paul at a hill just outside of Paris. When the church was completed Geneviève was buried within it. As numerous miracles started to occur at her tomb, the church was renamed Sainte-Geneviève. Plundered by the Normans during the ninth century, the church of Ste-Geneviève was later rebuilt and eventually completed in 1177.

In 1744, King Louis XV, while ill, followed the precedents set by his Bourbon forebears, and prayed to Sainte-Geneviève, promising to build a new ecclesiastical monument in her honor should she restore him to health. Louis's prayers were answered, and soon thereafter he directed his commissioner for public buildings, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, to begin planning the new edifice. The cornerstone for the new building was laid in 1764 by the king himself, but it was still under construction when the Revolution broke out in the summer of 1789.

Less than two years later, on April 4, 1791, the National Assembly decreed that the new Sainte-Geneviève be "destined to receive the ashes of Great Men." Shortly thereafter, the remains of the recently deceased National Assembly president Comte Honoré Gabriel Riqueti de Mirabeau, were translated into the newly re-consecrated Panthéon in the first highly publicized event centered around the church of Sainte-Geneviève since the onslaught of the Revolution. The shrine with the relics of Sainte Geneviève had meanwhile been transferred to the nearby Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, but it was eventually taken to the Hôtel des Monnaies, where it was dismantled and deposited in the national treasury. Following appraisal, the materials encasing the relics were valued at 23,830 livres.

In a macabre demonstration of the revolutionary regime's judicial authority, the saint's bones were put on trial and condemned to public burning, their crime being the "[participation] in the propagation of error." Having been subjected to a revolutionary auto-da-fé in Paris' Place de Grève on December 3, 1793, Sainte Geneviève's ashes were sanctimoniously cast into the Seine. Today, the church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont preserves portions of the saint's remains that had survived the Revolution in other locations.

Sainte-Chapelle

1242-48, Paris, France

Detail from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry by the Limbourg Brothers, an illuminated manuscript ca. 1400.

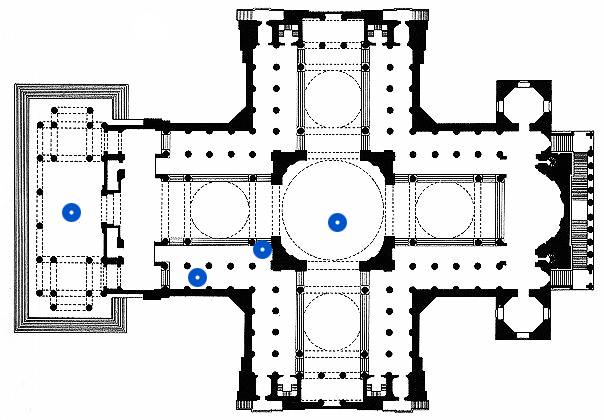

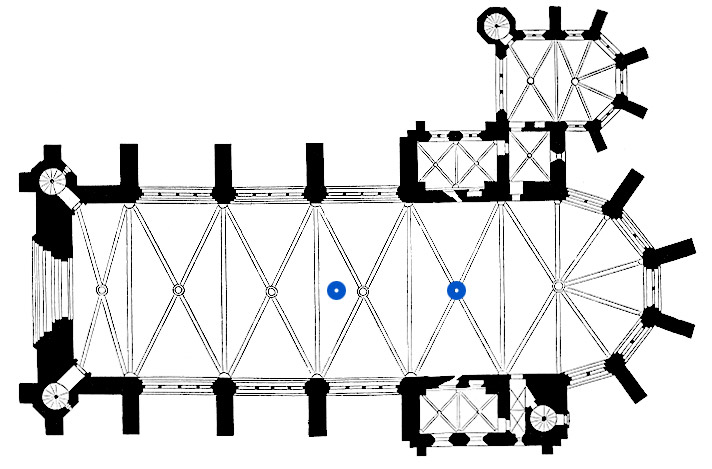

King Louis IX (r.1226-70) commissioned the Ste-Chapelle for the expressed purpose of exhibiting his many reliquary acquisitions—the greatest of which was the Crown of Thorns. The edifice was a two-part structure containing an upper and lower chapel. Each level consisted of four rectangular bays terminated by a seven-sided polygonal apse. The lower chapel contained two longitudinal rows of columnar supports that carried the floor of the vessel above. The upper chapel, in contrast, contained no freestanding vertical supports. Thick exterior buttresses bore its heavy structural loads and allowed the introduction of huge stained glass windows around the periphery of the building. The result was a cage-like space that one contemporary, Pope Innocent IV, aptly described as a giant reliquary.

The presence of an intricate screen, canopy, and large reliquary chest (the Grande Châsse) at the eastern end of the chapel only intensified such an interpretation. The canopy structure, like the Ste-Chapelle itself, had two levels: a lower niche that accommodated the main altar of the chapel and an upper platform, reached via two small octagonal staircases, whose canopy framed the Grande Châsse. The front end of the chest resembled a church facade; the back end was hollow and granted both visual and physical access to the Passion relics Louis stored there. Three key objects in this ensemble stood out: the Crown of Thorns, the True Cross, and the Holy Lance. Their location within a layered series of architectural containers—chapel, canopy, and chest—denoted their precious quality and distinguished Louis as ruler both powerful and pious.

An elaborate decorative program covering almost every interior surface of the upper chapel similarly advertised the wealth and devotion of the royal household. Sculpted angels and painted saints populated the spandrels of the wall arcade. Life-size statues of the apostles, affixed to shafted supports articulating each bay, resided between the wall and clerestory levels. Finally, highest of all, innumerable biblical, ecclesial, and dynastic figures occupied the dazzling clerestory windows illuminating the ornate chapel. The compaction of this overabundant imagery within a relatively unencumbered space confused the normally stable categories of time and place and thus conflated the king with a pantheon of holy figures from redemptive history. Such an effect—the mediation of multiple realities—ultimately reflected that of relics themselves and proved fitting for a purpose-built reliquary shrine.

Exhibition Objects Associated with Paris

- The Holy Thorn Reliquary

- Reliquary of Sts. Lucian, Maximian, and Julian

- Reliquary Pendant for the Holy Thorn

- Psalter Hours

- Panels from a Window Showing the Life and Martyrdom of St. Vincent of Sargossa

- Kneeling Prophet

- Virgin with the Christ Child